In brief: Security researchers have uncovered a chilling global epidemic: an old malware that has been spreading uncontrollably for years. Despite its creators seemingly abandoning the project years ago, this insidious USB worm has lived on, potentially infecting millions of new machines around the world.

The worm, which first hit the scene in 2019 as a new variant of the infamous PlugX malware, had a devious trick up its sleeve. It could automatically copy itself onto any USB drive connected to an infected machine, allowing it to hitch a ride and infect new computers without any user interaction required.

But at some point, the hackers abandoned the malware’s command-and-control server, essentially cutting off their ability to oversee the infected machines. One might assume this would be the end of the line for the pesky worm, but that was not the case.

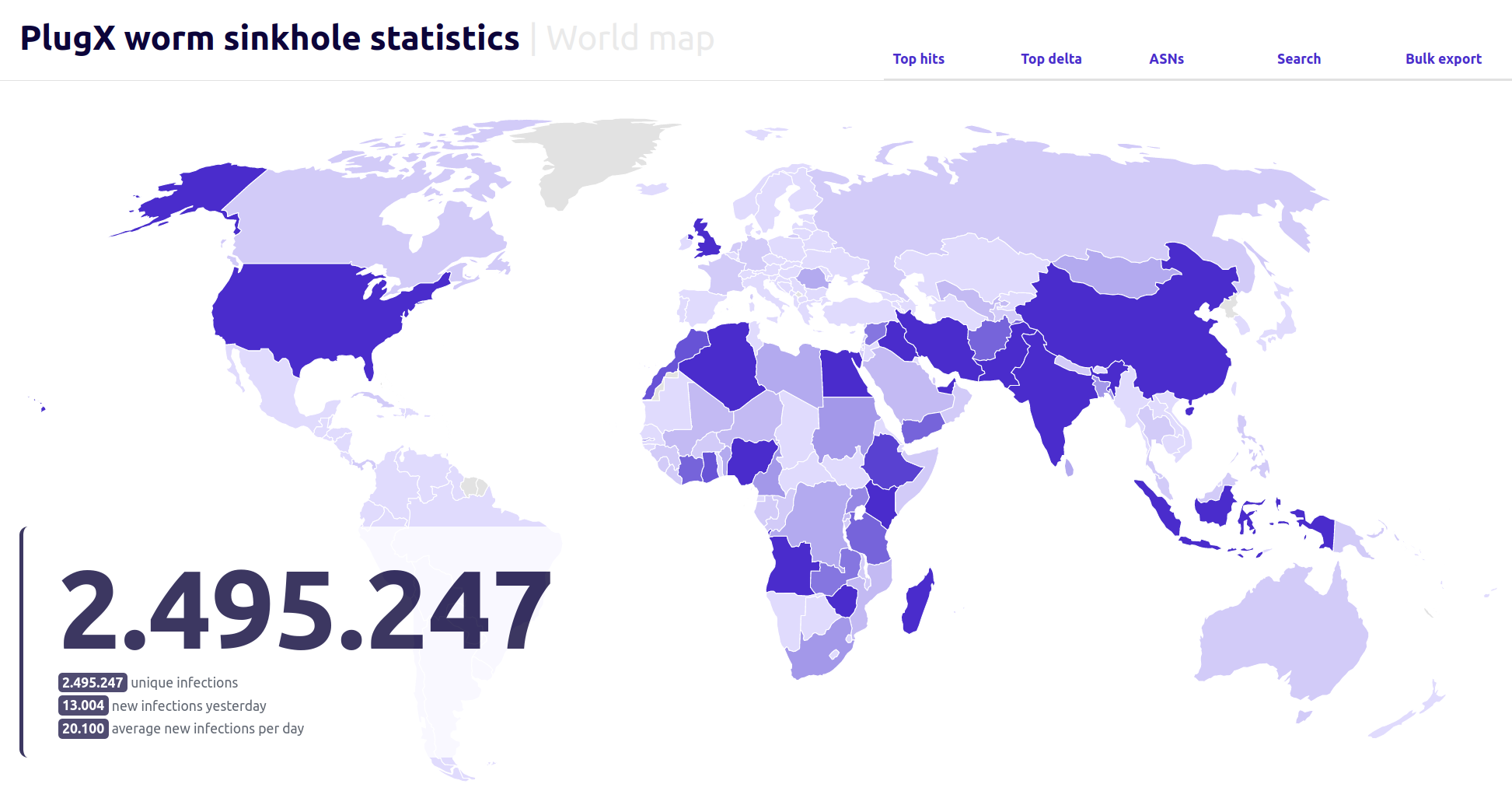

Researchers from security firm Sekoia decided to do some digital archaeology and purchased the abandoned IP address that was originally used to control the worm. To their surprise, they found the worm was still very much alive and kicking, with their server receiving connections from 90,000 to 100,000 unique IP addresses every single day. Over six months, they counted a staggering 2.5 million unique IPs trying to phone home.

It’s important to note that IP addresses don’t always accurately represent the total number of infected systems since some IPs could be shared by multiple devices or computers may use dynamic IPs. But the sheer volume of traffic suggests this worm has spread far and wide, potentially infecting millions of machines worldwide.

What’s even more intriguing is that the researchers found around 15 countries accounting for over 80% of the infections. And these aren’t just random nations – many have strategic importance and significant Chinese infrastructure investments. This has led to speculation that the worm may have been a Chinese intelligence-gathering operation targeting specific regions.

“It is plausible, though not definitively certain as China invests everywhere, that this worm was developed to collect intelligence in various countries about the strategic and security concerns associated with the Belt and Road Initiative, mostly on its maritime and economic aspects,” notes Sekoia.

Thankfully, the researchers did discover a potential solution: a command that could remove the malware from infected machines and even clean up any USB drives connected during the disinfection process. However, they decided against taking unilateral action due to legal concerns and have instead reached out to relevant authorities in affected countries, providing them with data and leaving the decision in their hands.

“Given the potential legal challenges that could arise from conducting a widespread disinfection campaign, which involves sending an arbitrary command to workstations we do not own, we have resolved to defer the decision on whether to disinfect workstations in their respective countries to the discretion of national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs), and cybersecurity authorities,” the researchers wrote.